Introduction to Aggregate Data Modeling with admr

This vignette provides a comprehensive introduction to using the

admr package for aggregate data modeling in population

pharmacokinetics. We’ll cover the basic concepts, data preparation,

model specification, and make a link to more advanced features.

What is Aggregate Data Modeling?

Aggregate data modeling is a new approach in pharmacometrics that allows you to work with summary-level data instead of individual-level observations. This is particularly useful when:

- Individual-level data is not available (e.g., from published literature)

- You need to combine data from multiple studies

- You want to perform meta-analyses

- You’re working with simulated data and want to reduce computational burden

The admr package implements the Iterative Reweighting

Monte Carlo (IRMC) algorithm, which efficiently fits models to aggregate

data by iteratively updating parameter estimates using weighted

importance sampling. This is more efficient than traditional Monte Carlo

methods.

Understanding the Data Format

The admr package works with two types of data

formats:

- Raw Data: Individual-level observations in a wide or long format.

- Aggregate Data: Summary statistics (mean and covariance) computed from raw data.

- Aggregate Data with only means and variance: Mean and variance for each time point (no covariances).

The vignette Variance-only based modelling provides more details on the third option.

Let’s look at the examplomycin dataset, which we’ll use throughout this vignette:

## ID TIME DV AMT EVID CMT

## 1 460 0.00 0.000 100 101 1

## 2 460 0.10 0.752 0 0 2

## 3 460 0.25 1.932 0 0 2

## 4 460 0.50 3.694 0 0 2

## 5 460 1.00 3.479 0 0 2

## 6 460 2.00 4.003 0 0 2## Number of subjects: 500## Number of time points: 10## Time points: 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 12Data Preparation

Converting Raw Data to Aggregate Format

The first step is to convert our simulated raw data into aggregate

format. In real-world scenarios, you might have to extract summary

statistics from published studies, depending on the available

information. But for this example, we’ll compute the mean and covariance

from the examplomycin dataset. Here’s how to do it:

# Convert to wide format

examplomycin_wide <- examplomycin %>%

filter(EVID != 101) %>% # Remove dosing events

dplyr::select(ID, TIME, DV) %>% # Select relevant columns

pivot_wider(names_from = TIME, values_from = DV) %>% # Convert to wide format

dplyr::select(-c(1)) # Remove ID column

# Create aggregated data

examplomycin_aggregated <- examplomycin_wide %>%

admr::meancov() # Compute mean and covariance

# View the structure of aggregated data

str(examplomycin_aggregated)## List of 2

## $ E: Named num [1:9] 0.966 1.939 2.788 3.025 2.258 ...

## ..- attr(*, "names")= chr [1:9] "0.1" "0.25" "0.5" "1" ...

## $ V: num [1:9, 1:9] 0.2103 0.3078 0.3486 0.2026 0.0224 ...

## ..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

## .. ..$ : chr [1:9] "0.1" "0.25" "0.5" "1" ...

## .. ..$ : chr [1:9] "0.1" "0.25" "0.5" "1" ...This aggregated data now contains the mean concentrations and the

covariance matrix at each time point. If you have raw data, you can use

the meancov function to compute these statistics. However,

when extracting data from literature, you may need to manually input the

means and covariances based on the reported values. If only standard

deviations are available, you can construct a diagonal covariance

matrix.

Visualizing the Data

Before fitting the model, it’s helpful to visualize the aggregate data:

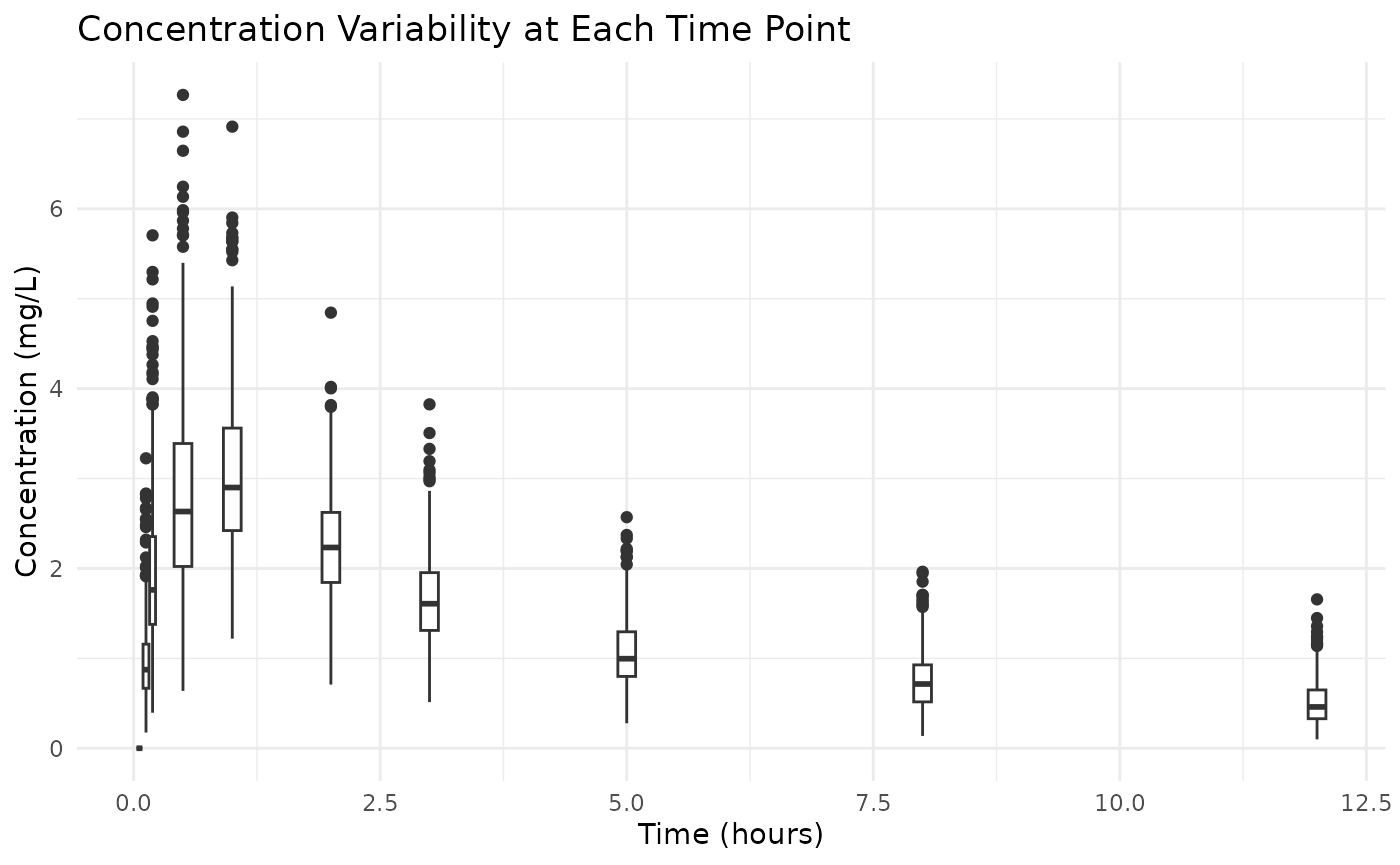

# Boxplot to visualize variability

ggplot(examplomycin, aes(x = TIME, y = DV, group = TIME)) +

geom_boxplot(aes(group = TIME), width = 0.2) +

labs(

title = "Concentration Variability at Each Time Point",

x = "Time (hours)",

y = "Concentration (mg/L)"

) +

theme_minimal()

This plot doesn’t show the covariance between time points, but it gives an idea of the variability in concentrations at each time point.

Model Specification

Defining the Pharmacokinetic Model

We’ll use a two-compartment model with first-order absorption. There are two ways to specify this:

- Using differential equations:

Click here

rxModel <- function(){

model({

# Parameters

ke = cl / v1 # Elimination rate constant

k12 = q / v1 # Rate constant for central to peripheral transfer

k21 = q / v2 # Rate constant for peripheral to central transfer

# Differential equations

d/dt(depot) = -ka * depot

d/dt(central) = ka * depot - ke * central - k12 * central + k21 * peripheral

d/dt(peripheral) = k12 * central - k21 * peripheral

# Concentration in central compartment

cp = central / v1

})

}

rxModel <- rxode2(rxModel)

rxModel <- rxModel$simulationModel- Using the solved model approach (simpler):

Click here

These models are identical in terms of their pharmacokinetic

behavior. The second approach is the solved model, which is faster in

execution. In this stage of package development, it is important the

parameters are in the same order as specified in the

genopts function later.

Creating the Prediction Function

The prediction function is crucial for the admr package.

It: - Constructs the event table for dosing and sampling - Solves the

rxode2 model - Returns predicted concentrations in the required

format

rxode2::rxSetSilentErr(1) # does not print iteration messages in vignette## [1] TRUE

predder <- function(time, theta_i, dose = 100) {

n_individuals <- nrow(theta_i)

if (is.null(n_individuals)) {

n_individuals <- 1

}

# Create event table

ev <- eventTable(amount.units="mg", time.units="hours")

ev$add.dosing(dose = dose, nbr.doses = 1, start.time = 0)

ev$add.sampling(time)

# Solve model

out <- rxSolve(rxModel, params = theta_i, events = ev, cores = 0)

# Format output

cp_matrix <- matrix(out$cp, nrow = n_individuals, ncol = length(time),

byrow = TRUE)

return(cp_matrix)

}This is the function that admr will use to generate

predictions based on the model parameters. The user can specify the dose

amount, number of doses and the dosing interval in the

eventTable function. Furthermore, the rxSolve

function can be parallelized by setting the cores argument

to a value greater than 1, which can significantly speed up computations

for large datasets or complex models.

Model Fitting

Setting Up Model Options

The genopts function creates an options object that

controls the model fitting process:

opts <- genopts(

time = c(.1, .25, .5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 12), # Observation times

p = list(

beta = c(cl = 4, v1 = 12, v2 = 25, q = 12, ka = 1.2), # Population parameters

Omega = matrix(c(0.09, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0.09, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0.09, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0.09, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0.09), nrow = 5, ncol = 5), # Random effects

Sigma_prop = 0.04 # Proportional error

),

nsim = 10000, # Number of Monte Carlo samples

n = 500, # Number of individuals

fo_appr = F, # Disable first-order approximation used in lower nsim

omega_expansion = 1, # Omega expansion factor

f = predder # Prediction function we defined earlier

)In this opts object:

time: Specifies the observation timesp: Contains the initial estimates for population parameters (beta), between-subject variability (Omega), and residual error (Sigma_prop)nsim: Number of Monte Carlo samples to use in the fitting processn: Number of individuals to simulatefo_appr: Whether to use a first-order approximationomega_expansion: A factor to expand the covariance matrix during estimation, which can help with convergencef: The prediction function we defined earlier

Fitting the Model

The fitMC function fits the model using a traditional MC

algorithm:

fit.admrMC <- fitMC(

opts = opts,

obs = examplomycin_aggregated,

chains = 1, # Number of chains

maxiter = 2000, # Maximum iterations

use_grad = T

)## Iteration: 5 - NLL: 16801.59

## Iteration: 10 - NLL: -1840.397

## Iteration: 15 - NLL: -1844.982

## Iteration: 20 - NLL: -1845.272

## Iteration: 25 - NLL: -1845.317

## Iteration: 30 - NLL: -1845.341

## Iteration: 35 - NLL: -1845.355

## Iteration: 40 - NLL: -1845.357

##

## Chain 1 Complete: Final NLL = -1845.357, Time Elapsed = 71.11 secondsThe fitIRMC function fits the model using the IRMC

algorithm, which is more efficient for aggregate data:

fit.admr <- admr::fitIRMC(

opts = opts,

obs = examplomycin_aggregated,

chains = 1, # Number of chains

maxiter = 200, # Maximum iterations

use_grad = T

)## Chain 1:

## Iter | NLL and Parameters (11 values)

## --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## 1: -1587.397 1.386 2.485 3.219 2.485 0.182 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -3.219

##

## ### Wide Search Phase ###

## 2: -1844.307 1.605 2.273 3.425 2.276 -0.014 -2.201 -2.213 -2.203 -2.271 -2.416 -3.236

## 3: -1845.352 1.601 2.311 3.403 2.285 0.021 -2.285 -2.206 -2.346 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 4: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.346 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 5: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.345 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 6: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.345 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 7: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.345 -2.246 -2.399 -3.235

## 8: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.283 -2.206 -2.345 -2.246 -2.399 -3.235

## 9: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.022 -2.283 -2.206 -2.344 -2.246 -2.399 -3.235

## 10: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.022 -2.283 -2.206 -2.344 -2.246 -2.399 -3.235

## 11: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.283 -2.209 -2.337 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## 12: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.209 -2.337 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## Phase Wide Search Phase converged at iteration 12.

##

## ### Focussed Search Phase ###

## 13: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.209 -2.337 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## 14: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## 15: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## 16: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## Phase Focussed Search Phase converged at iteration 16.

##

## ### Fine-Tuning Phase ###

## 17: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.396 -3.235

## 18: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 19: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 20: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 21: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 22: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 23: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 24: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 25: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 26: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 27: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## Phase Fine-Tuning Phase converged at iteration 27.

##

## ### Precision Phase ###

## 28: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## Phase Precision Phase converged at iteration 28.

##

## Chain 1 Complete: Final NLL = -1845.353, Time Elapsed = 17.95 seconds

## Model Diagnostics

Basic Diagnostics

The print method provides a summary of the model

fit:

print(fit.admr)## -- FitIRMC Summary --

##

## -- Objective Function and Information Criteria --

## Log-likelihood: -1845.3535

## AIC: 3701.71

## BIC: 3759.07

## Condition#(Cov): 150.83

## Condition#(Cor): 214.64

##

## -- Timing Information --

## Best Chain: 17.9518 seconds

## All Chains: 17.9542 seconds

## Covariance: 23.7759 seconds

## Elapsed: 41.73 seconds

##

## -- Population Parameters --

## # A tibble: 6 × 6

## Parameter Est. SE `%RSE` `Back-transformed(95%CI)` `BSV(CV%)`

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 cl 1.60 0.0152 0.950 4.96 (4.81, 5.11) 31.9

## 2 v1 2.32 0.0861 3.71 10.15 (8.57, 12.01) 33.1

## 3 v2 3.40 0.0399 1.17 30.00 (27.74, 32.45) 31.1

## 4 q 2.29 0.0212 0.928 9.83 (9.43, 10.24) 32.7

## 5 ka 0.0263 0.0813 309. 1.03 (0.88, 1.20) 30.2

## 6 Residual Error 0.0394 NA NA 0.0394 NA

##

## -- Iteration Diagnostics --

## Iter | NLL and Parameters

## --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## 1: -1587.397 1.386 2.485 3.219 2.485 0.182 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -2.408 -3.219

## 2: -1844.307 1.605 2.273 3.425 2.276 -0.014 -2.201 -2.213 -2.203 -2.271 -2.416 -3.236

## 3: -1845.352 1.601 2.311 3.403 2.285 0.021 -2.285 -2.206 -2.346 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 4: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.346 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## 5: -1845.353 1.601 2.312 3.403 2.284 0.021 -2.284 -2.206 -2.345 -2.247 -2.399 -3.235

## ... (omitted iterations) ...

## 24: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.210 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 25: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 26: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

## 27: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235

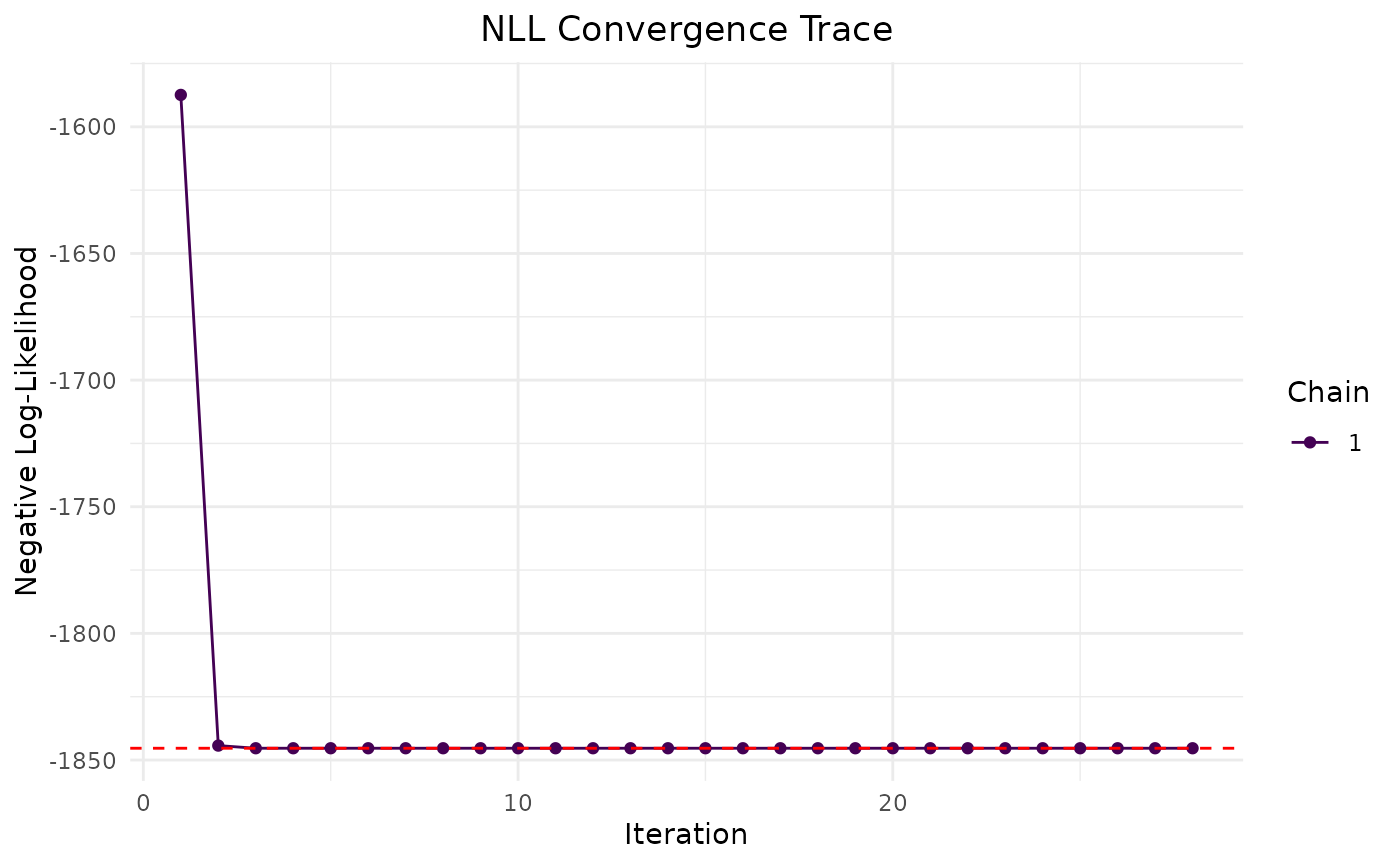

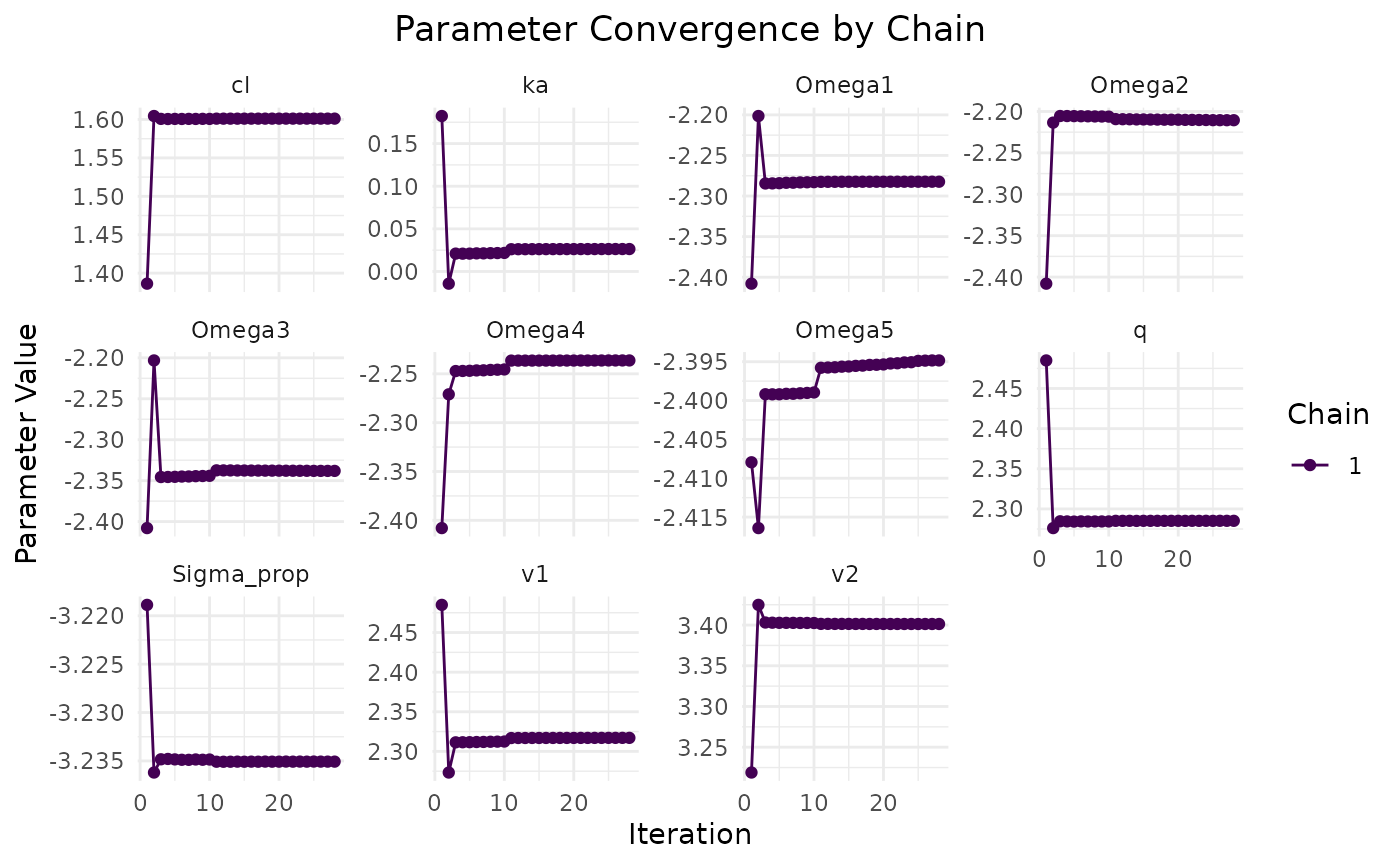

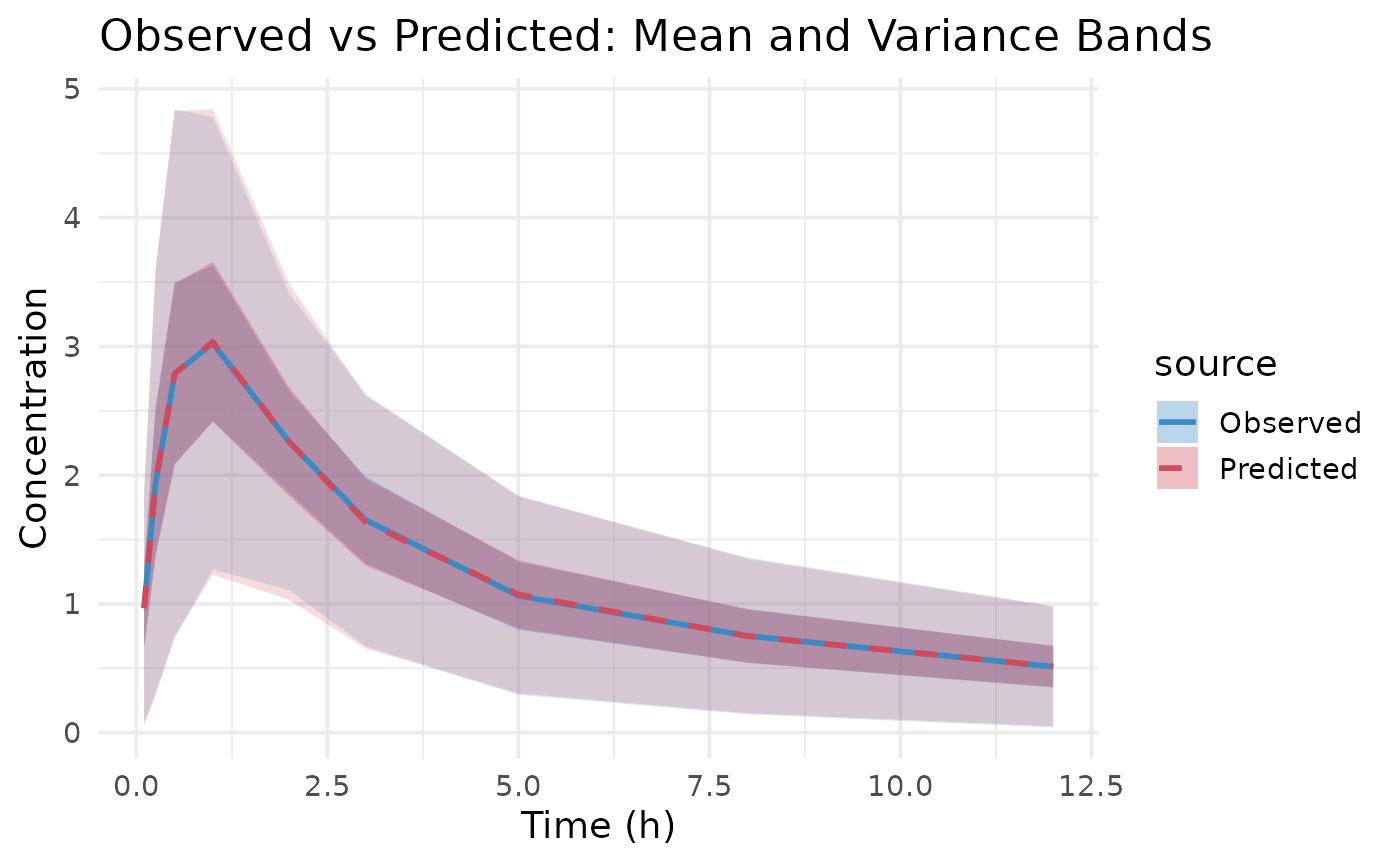

## 28: -1845.353 1.601 2.317 3.401 2.285 0.026 -2.282 -2.211 -2.338 -2.236 -2.395 -3.235Convergence Assessment

The plot method visualizes the convergence of the model

fit:

plot(fit.admr)

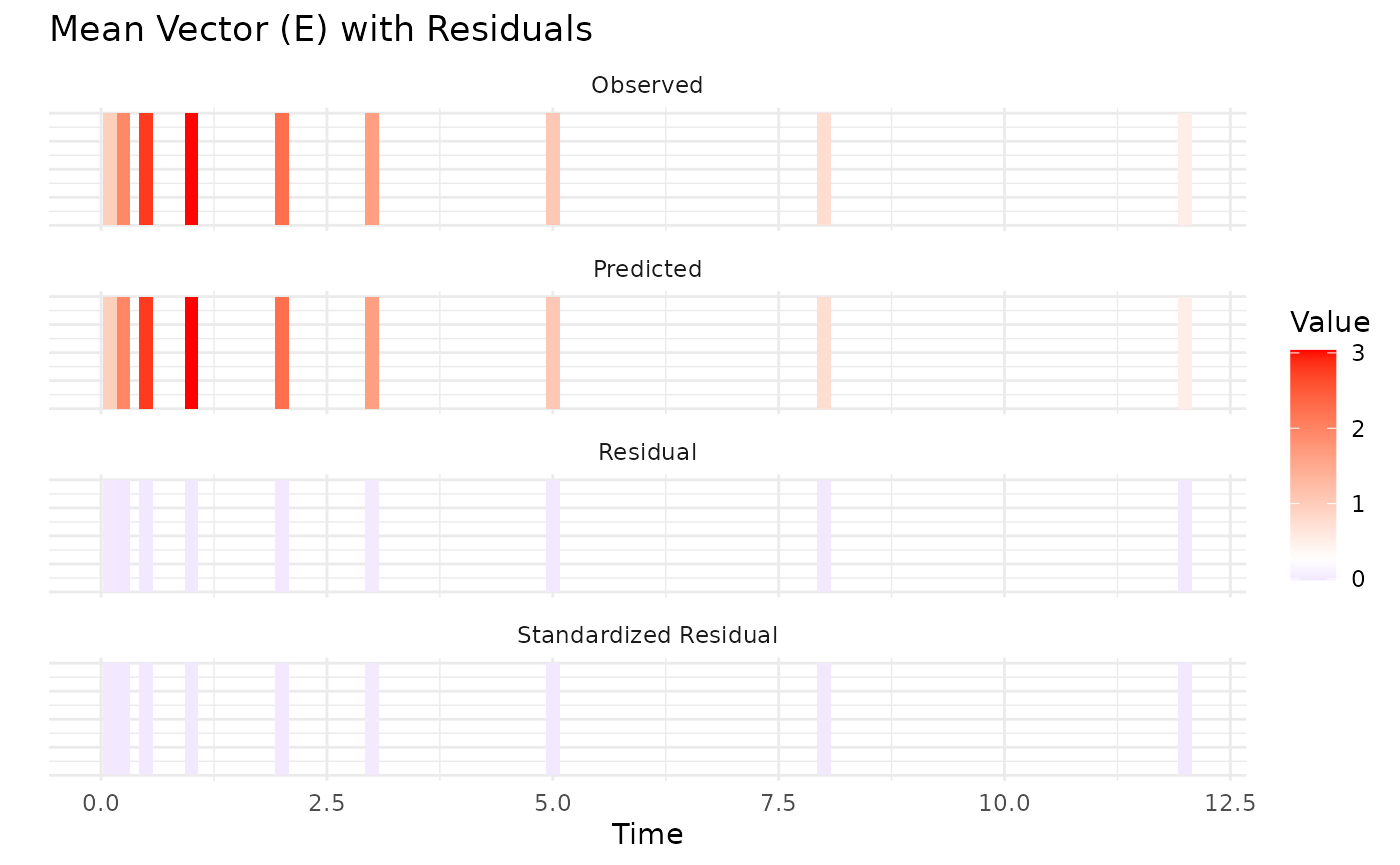

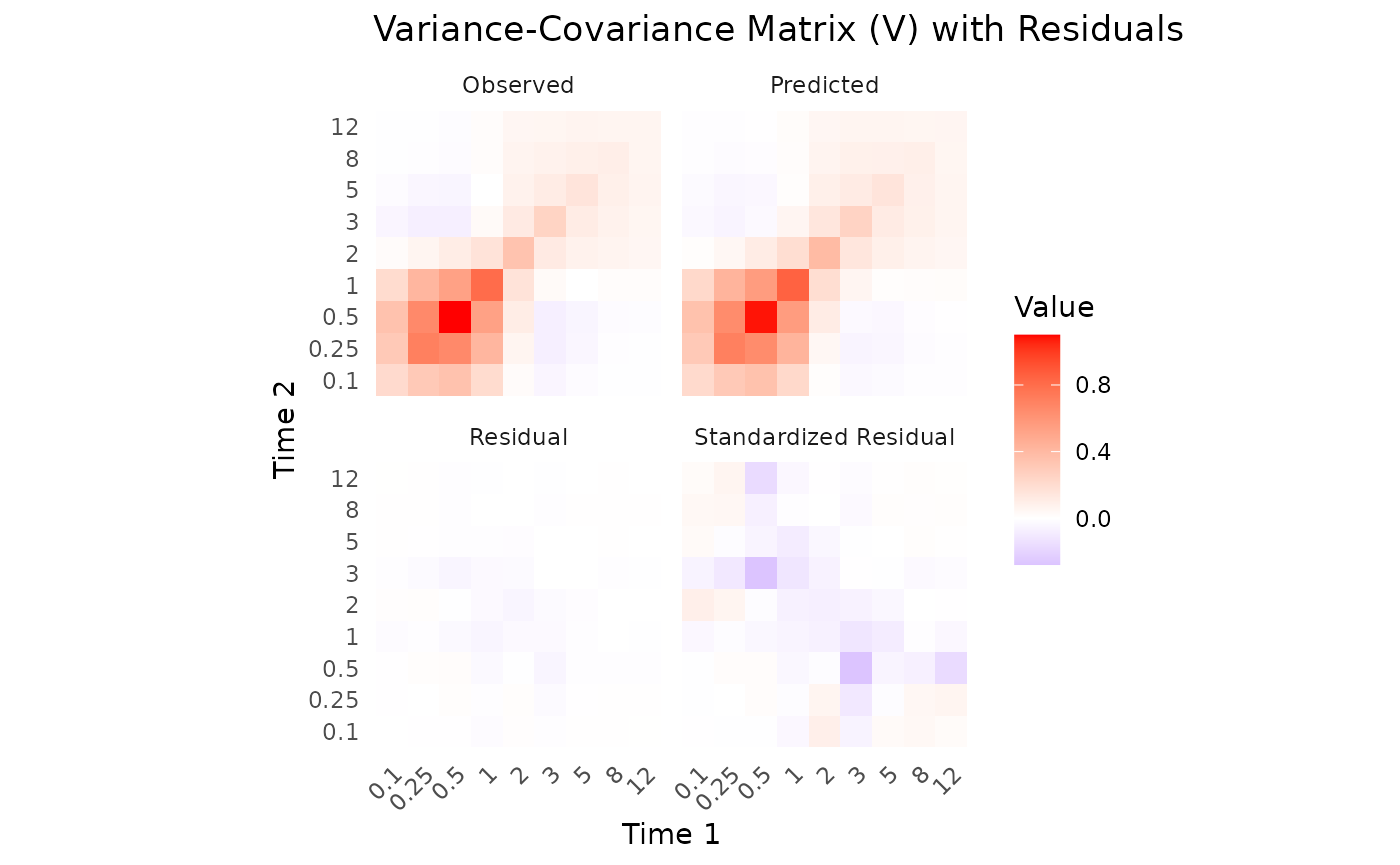

The Observed vs Predicted plot shows how well the model predictions align with the observed aggregate data. These show a good fit to the data, with means and variability well captured. However, let’s examine the parameter estimates for a more detailed assessment. The predicted means and variance-covariance show good resemblance to the observed data, indicating that the model is capturing the underlying pharmacokinetic behavior effectively.

Parameter Estimates

Let’s examine the parameter estimates:

# Extract parameter estimates

params <- fit.admr$transformed_params

cat("Final parameter estimates:\n")## Final parameter estimates:

print(params)## $beta

## cl v1 v2 q ka

## 4.958566 10.145764 30.003901 9.827655 1.026681

##

## $Omega

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 0.1020431 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.00000000

## [2,] 0.0000000 0.1096415 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.00000000

## [3,] 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0965136 0.0000000 0.00000000

## [4,] 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.1068517 0.00000000

## [5,] 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.09118536

##

## $Sigma_prop

## [1] 0.03935747

params.true <- list(

beta = c(cl = 5, v1 = 10, v2 = 30, q = 10, ka = 1),

Omega = diag(rep(0.09, 5)),

Sigma_prop = 0.04

)

cat("True parameter values:\n")## True parameter values:

print(params.true)## $beta

## cl v1 v2 q ka

## 5 10 30 10 1

##

## $Omega

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 0.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

## [2,] 0.00 0.09 0.00 0.00 0.00

## [3,] 0.00 0.00 0.09 0.00 0.00

## [4,] 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.09 0.00

## [5,] 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.09

##

## $Sigma_prop

## [1] 0.04For this dataset, the estimated parameters are close to the true values used in the simulation, indicating a successful model fit using only summary statistics. However, small discrepancies can occur due to the stochastic nature of the Monte Carlo sampling and the limited number of samples. Therefore, we’ll assess the overall dynamics of the model through a dosing simulation.

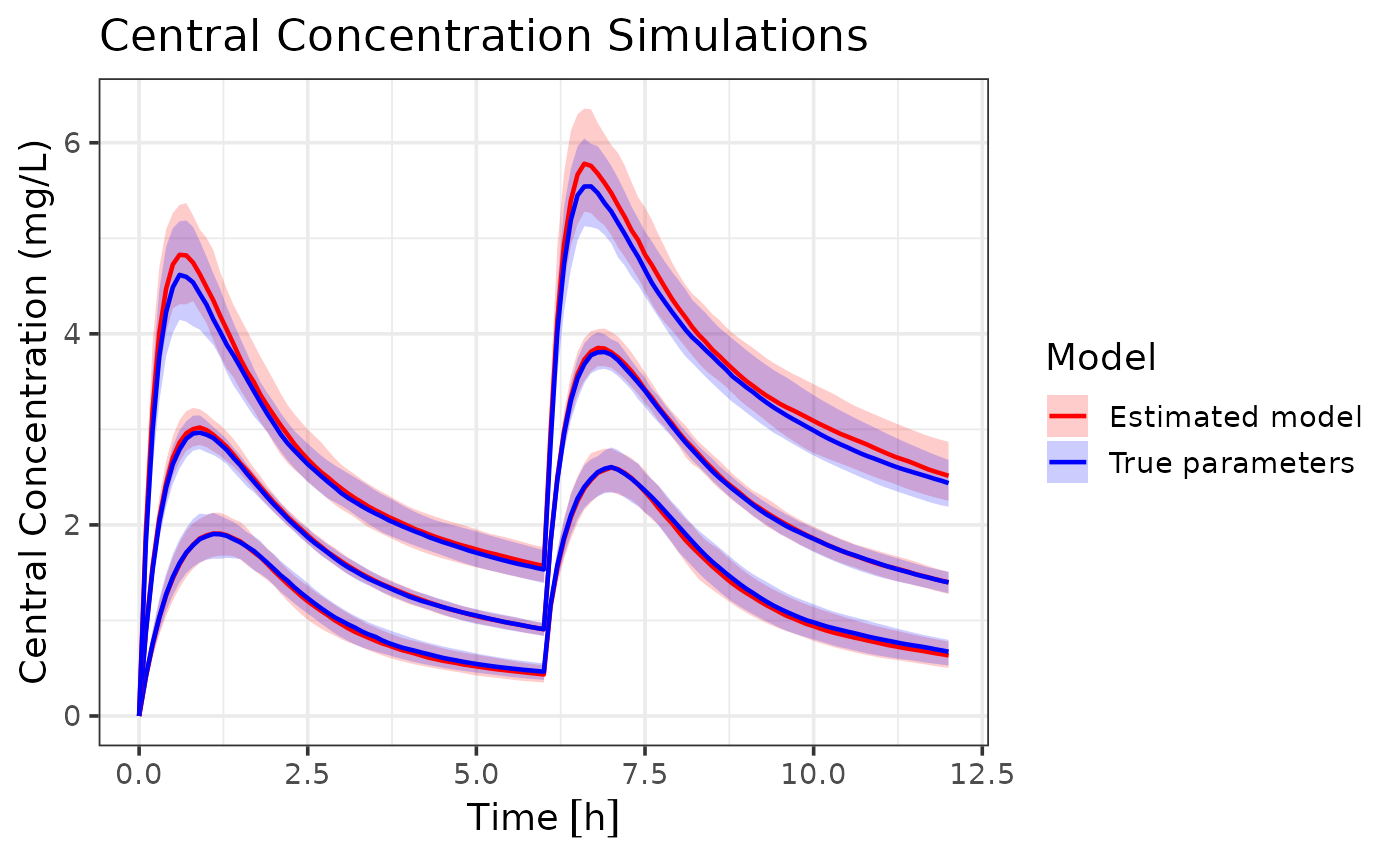

Dosing plot with Confidence Intervals for true vs estimated parameters

First, let’s specify two models: one with the true parameters and

another with the estimated parameters from the fit.admr

object.

Click here

params.true <- list(

beta = c(cl = 5, v1 = 10, v2 = 30, q = 10, ka = 1),

Omega = diag(rep(0.09, 5)),

Sigma_prop = 0.04

)

params <- fit.admr$transformed_params

rxModel_true <- function(){

ini({

cl <- params.true$beta["cl"] # Clearance

v1 <- params.true$beta["v1"] # Volume of central compartment

v2 <- params.true$beta["v2"] # Volume of peripheral compartment

q <- params.true$beta["q"] # Inter-compartmental clearance

ka <- params.true$beta["ka"] # Absorption rate constant

eta_cl ~ params.true$Omega[1,1]

eta_v1 ~ params.true$Omega[2,2]

eta_v2 ~ params.true$Omega[3,3]

eta_q ~ params.true$Omega[4,4]

eta_ka ~ params.true$Omega[5,5]

})

model({

cl <- cl * exp(eta_cl)

v1 <- v1 * exp(eta_v1)

v2 <- v2 * exp(eta_v2)

q <- q * exp(eta_q)

ka <- ka * exp(eta_ka)

cp = linCmt(cl, v1, v2, q, ka)

})

}

rxModel_covar <- function(){

ini({

cl <- params$beta["cl"] # Clearance

v1 <- params$beta["v1"] # Volume of central compartment

v2 <- params$beta["v2"] # Volume of peripheral compartment

q <- params$beta["q"] # Inter-compartmental clearance

ka <- params$beta["ka"] # Absorption rate constant

eta_cl ~ params$Omega[1,1]

eta_v1 ~ params$Omega[2,2]

eta_v2 ~ params$Omega[3,3]

eta_q ~ params$Omega[4,4]

eta_ka ~ params$Omega[5,5]

})

model({

cl <- cl * exp(eta_cl)

v1 <- v1 * exp(eta_v1)

v2 <- v2 * exp(eta_v2)

q <- q * exp(eta_q)

ka <- ka * exp(eta_ka)

cp = linCmt(cl, v1, v2, q, ka)

})

}

rxModel_true <- rxode2(rxModel_true())

rxModel_true <- rxModel_true$simulationModel

rxModel_covar <- rxode2(rxModel_covar())

rxModel_covar <- rxModel_covar$simulationModelNow, let’s simulate both models over a dosing regimen and plot the results with confidence intervals:

time_points <- seq(0, 12, by = 0.1) # Dense time points for smooth curves

ev <- eventTable(amount.units="mg", time.units="hours")

ev$add.dosing(dose = 100, nbr.doses = 2, dosing.interval = 6)

ev$add.sampling(time_points)

sim_true <- rxSolve(rxModel_true, events = ev, cores = 0, nSub = 10000)

sim_covar <- rxSolve(rxModel_covar, events = ev, cores = 0, nSub = 10000)

# Combine the confidence intervals with a label for the model

ci_true <- as.data.frame(confint(sim_true, "cp", level=0.95)) %>%

mutate(Model = "True parameters")## summarizing data...done

ci_covar <- as.data.frame(confint(sim_covar, "cp", level=0.95)) %>%

mutate(Model = "Estimated model")## summarizing data...done

# Bind them together

ci_all <- bind_rows(ci_true, ci_covar) %>%

mutate(

p1 = as.numeric(as.character(p1)),

Percentile = factor(Percentile, levels = unique(Percentile[order(p1)]))

)

# Plot both models

ggplot(ci_all, aes(x = time, group = interaction(Model, Percentile))) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = p2.5, ymax = p97.5, fill = Model),

alpha = 0.2, colour = NA) +

geom_line(aes(y = p50, colour = Model), size = 0.8) +

labs(

title = "Central Concentration Simulations",

x = "Time",

y = "Central Concentration (mg/L)"

) +

theme_bw(base_size = 14) +

scale_colour_manual(values = c("True parameters" = "blue",

"Estimated model" = "red")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("True parameters" = "blue",

"Estimated model" = "red"))## Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

## ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

## This warning is displayed once per session.

## Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was

## generated.

We can see that the model with estimated parameters closely follows

the dynamics of the model with true parameters, indicating that the

admr package can effectively recover population parameters

from aggregate data. These are some small differences in the 95%

population and their associated confidence intervals, showing slight

overestimation of random effects. However, the overall dynamics are well

captured.

Best Practices

-

Data Preparation:

- Always check your data for missing values and outliers

- Ensure time points are consistent across subjects

- Consider the impact of dosing events on your analysis

-

Model Specification:

- Start with a simple model and gradually add complexity

- Use meaningful initial values for parameters

- Consider parameter transformations for better estimation

-

Model Fitting:

- Use multiple chains to improve optimization

- Monitor convergence carefully

- Check parameter estimates for biological plausibility

-

Diagnostics:

- Always examine convergence plots

- Validate model predictions against observed data